= = =

The Franco-Prussian War saw the first use of aircraft for wartime evacuation. During the Siege of Paris in 1870 and 1871,

a hundred wealthy citizens flew out of the city via balloon, sitting on bags of mail.

Using helicopters for last-minute evacuation under fire was rare during the first 15 years of wartime use, beginning in Burma during World War II, then in Korea, Malaya, French Indochina, and Algeria. Instead helicopters hauled reinforcements and ammunition to the battlefield and took wounded men from field-dressing stations. Here's a photo of French helo pilot Valerie Andre from www.aerodrome-gruyere.ch.

During the Vietnam War, helicopters would take on a new job as getaway vehicles, most famously during the final evacuation of Americans (and selected allies) from Saigon in 1975.

One trend-setting incident came ten years earlier, when Marine helicopters evacuated the entire population in and around Khe Tre in the face of oncoming Vietcong forces. Helicopters grabbed up 2,600 people and all their belongings, down to dogs, bags of rice, and bales of tobacco.

Also about this time, combat rescue by rotorcraft was developing on the other side of the demilitarized zone, deep inside North Vietnam and along the northern reaches of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The demand arose because the Air Force and Navy were making bombing runs over North Vietnam, and downed pilots needed help.

Any pilot or crewman dropping deep into the territory of a very angry enemy faced death or a long and brutal captivity. Their hopes rode with the Air Force’s 38th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service, known as the Jolly Greens because of the hulking look of their Sikorsky HH-3 rescue helicopter.

Jolly Greens did their work without the usual gunnery on board, but had backup from Douglas A-1 Skyraiders, a slow-flying propeller-driven airplane that was well-suited for strafing.

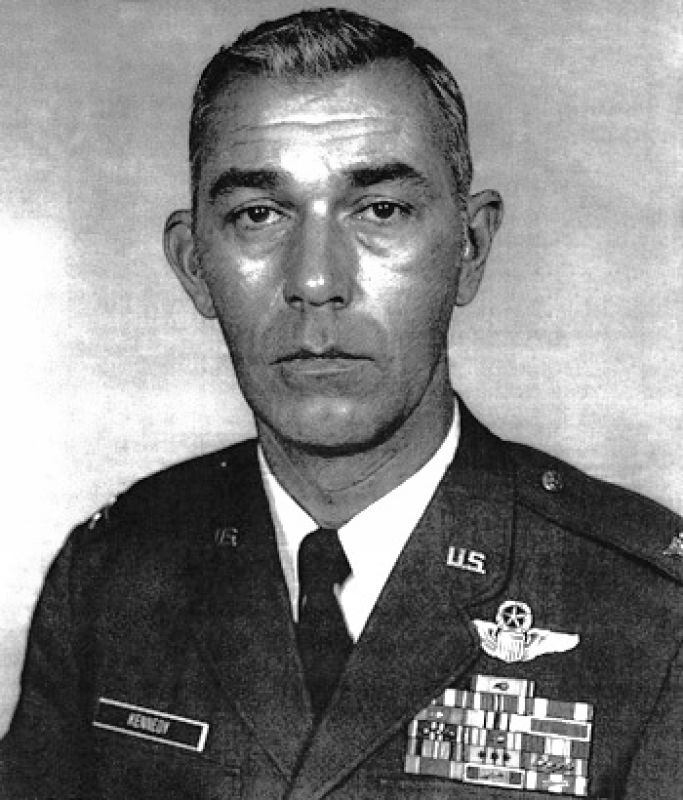

One of the Jolly Greens’ most highly decorated pilots was Capt. Leland Kennedy, who on October 5, 1966, was to receive the call to duty. It would win him an Air Force Cross, the service’s second-highest decoration. That day an F-4C Phantom (call sign: Tempest Three) was flying west of Hanoi, escorting an electronic-warfare aircraft back to base, when a MiG fired a heat-seeking missile from behind. The missile flew up the tailpipe and destroyed the engine, but without exploding. Phantoms look like this:

“This was over a really bad area,” Ed Garland told me. Garland occupied the rear seat that day. “There were two rivers on the northwest, the Red and Black Rivers. If you were north of the Red, the standing order was: ‘No pickups there, it’s too dangerous.’”

Nursing their airplane as far south as possible to aid any rescuers, the two pilots waited till they saw the Red River, then ejected. Lt. Garland’s chute dropped him on a mountainside that was 45 miles south of Hanoi. That put him 300 miles from his fighter base. He had a pistol, a short-range radio, a bleeding ankle, and a back injury. A jet passed low overhead and began strafing the ground nearby; it was an F-105 Thunderchief pilot who had by a rare chance seen the Phantom’s smoke trail, had watched the parachutes descend, and had called for rescue. The message was relayed to Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base.

Two Jolly Green helicopters lifted off from a forward staging area along the Laos border. (Called Lima sites, these were positioned in Laos as close as possible to the North Vietnamese border and greatly extended the Jolly Greens’ working range.)

On his way down, Garland had seen a radar station atop the mountain's peak. Now he heard soldiers from that station coming down the slope, shooting and closing in, despite the Thunderchief’s strafing. Though Garland would be on the ground for a full four hours, the enemy held back from capturing him. He learned the reason later: he was bait in a trap. The North Vietnamese were placing heavy machine guns for the helicopters they knew would be coming.

Garland received a last radio message from his counterpart, Bill Andrews, on the other side of the mountain: Andrews had been hit in the chest; he was losing unconsciousness; and he would shoot up his radio to prevent the enemy from luring rescuers with it. (False radio calls, even NVA soldiers dressed in American flight suits, were common methods to lure helicopters into traps).

When Kennedy’s helicopter (Jolly Green Two) left its forward base it was supposed to serve only as escort, known as the “high bird” position, while Capt. Oliver O’Mara and crew in the primary helicopter, the “low bird,” carried out the rescue.

When the two helicopters arrived, says Garland, “the low bird came in and it drew small arms fire from rifles and machine guns ... anything they had.” By O’Mara’s third attempt to get a rescue seat to Garland on the mountainside, enemy gunfire had destroyed the helicopter’s hoist, shot up the fuselage, and damaged one engine. Tagged out, O’Mara flew off.

Kennedy was flying high bird that day because he was still a novice in the rescue business. It was Kennedy's eighth mission out of Udorn, but this would be his first actual rescue attempt.

The unfavorable circumstances were looking very similar to a tragic rescue attempt in September 1965 by another helicopter from the 38th, call sign Duchy 41. As Duchy 41 hovered in a box canyon, heavy machine-gun fire from above had shot it down. All five crewmen had been captured by Communist forces (See "Commissioned in Hanoi," Air Force Magazine).

Compounding the difficulty for Kennedy’s Jolly Green Two, the four Skyraiders that had been strafing to hold back the enemy were almost out of ammunition. This left Kennedy’s helicopter with only one advantage, a fogbank. Kennedy started his first run, using the fog as cover from heavy machine guns on the high ground, the Russian-made DShK:

A grenade or missile exploded in the Jolly's cabin, stunning pararescueman CMSgt. Ed Williamson. Williamson called out that he was fine and needed only help getting soot out of his eyes. Kennedy backed away and waited for Williamson to regain his sight. The Skyraiders radioed that they were dry on ammunition but would make low passes to frighten the enemy.

Kennedy made his second run: the fusillade from the ground punched more holes in the helicopter and put a bullet in Williamson’s knee. Kennedy retreated again and polled the crew: that had been the Jolly Greens’ fifth try. Did they want to cheat death once more? They crew voted in the affirmative. This time Kennedy lowered the jungle penetrator to the ground on its cable, and dragged it toward Garland as if trolling for a bottom-dwelling fish.

“I could see the helo now,” Garland recalls. “He didn’t have much cable out, maybe fifty feet. All the guns were firing at him. I ran maybe thirty or forty feet and pulled the seat down.”

Kennedy snatched him off the ground and rose toward the protective fog. There was one final thrill: Aboard the Jolly Green, Williamson looked down with horror at the sight of Garland’s parachute, rising in tandem with the airman. Somehow the shrouds or harness had tangled with rescue seat. As soon as the helicopter accelerated the parachute canopy was going to sweep back and tangle the tail rotor, which would send the helicopter spinning out of control. Perhaps these men were linked by telepathy, as only saved and savior can be, or perhaps not: in any case, Garland realized the problem instantly and yanked the parachute loose.

His helicopter low on fuel, Kennedy headed back to his Lima site. He won a second Air Force Cross two weeks later for another rescue in North Vietnam. He was the first airman to receive it twice.

No comments:

Post a Comment