Bill Gates has this OpEd about the solving world's toughest problems and why measurement makes a difference. Says he:

"In the past year, I have been struck by how important measurement is to improving the human condition. You can achieve incredible progress if you set a clear goal and find a measure that will drive progress toward that goal ..."

Perhaps measurement and commitment can be enough ... as long as it's not a wicked problem. Policy wonks often use that term to describe an interlinked nest of dilemmas that resists

all straightforward solutions. Thoroughly wicked examples from

today's headlines include international drug trafficking, medical

cost control, and runaway global warming.

Why so wicked? Entrenched

interests lie deep inside. Such interests are happy with the current

situation, and they know how to scratch up would-be reformers. It's

why B'rer Rabbit loved his patch of thorns.

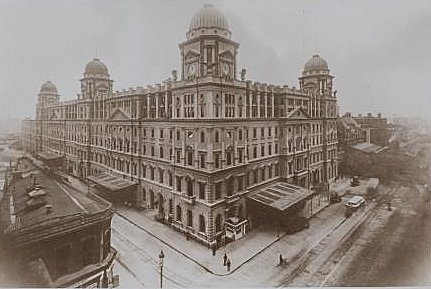

Athough the phrase hadn't been invented

in 1903, “wicked problem” described a set of hazards growing up

around a railroad terminal at 42nd Street in Midtown

Manhattan. Even so, regulators, engineers, and the New York Central

came together to craft a world-class solution. Just as visitors

marveled at shafts of sunlight through the high windows, Grand

Central threw new light on breakthrough problem-solving. (Photo © Royal Geographical Society, London, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library)

The lessons

are still useful one hundred years after the complex opened in

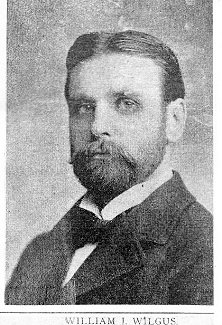

February 1913. It wouldn't have happened without an

unreasonable man, a brilliant and self-taught engineer by the name of William J. Wilgus.

While the

big ground-level railyard cut apart the neighborhoods and the steam

engines showered the neighborhoods with ash, New York Central refused

to do any more than renovate its station to pack in more passengers.

The station was profitable but posed many risks to passengers,

trainmen, and nearby residents.

Things began to change on January 8,

1902, when one steam engine in a tunnel leading to the station

smashed into another train that had stopped. The incoming train’s

engineer couldn't see the danger signal for all the smoke and steam.

All the papers covered the fatalities in horrifying detail, and the

New York City Council, working with the state legislature, ordered

that operations at the station shift from steam power to electric.

The city gave the railroad five years to finish the job.

At this early stage, just making the

sudden switch from steam to electric power would be a huge headache.

Certainly no reasonable person could have expect the railroad to

triple its workload by choosing to tear down its newly renovated

station and to rip up the half-mile long railyard to the north so it

could be put into a big hole. And to restore the streets. And to keep

daily traffic moving through the station even as it was torn down and

rebuilt. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Fortunately for posterity, William

Wilgus was simultaneously unreasonable and pragmatic. Born in Buffalo

in 1865, he had risen to the position of chief engineer and vice

president of the sprawling Vanderbilt-owned railroad network.

In one remarkable September afternoon,

eight months after the rail disaster, Wilgus sat down at his desk and

listed all the biggest problems facing the railroad and its station.

In a few hours, with one Eureka moment after another, he arrived at

an elegant solution: not just a win-win, but a win-win-win.

Wilgus started with the bitter fact

that government was forcing the railroad to do something it hadn't

wanted to do: shift quickly from steam to electrical power. While

that seemed a bad thing for the railroad's bottom line – don't Ayn

Randians tell us that all government mandates are outrageous? –

Wilgus saw that shifting to electric power might be a good thing.

Maybe a great thing. Why?

Electric power opened up entirely new

options. One option was putting buildings on beams over the railyard,

since the occupants wouldn't be smoked out by steam engines. But why

not sink the railyard below street level and put the new buildings at

street level instead? Wilgus realized that if he took the railyard

deep enough to split the underground rail traffic into two levels,

and added loops around the new station, this would greatly improve

the traffic flow. Before the sun set that day, Wilgus drew a plan

that would meet the government deadline, more than double the

station’s passenger capacity, transform midtown Manhattan, and turn

a liability to an immensely valuable asset.

Wilgus advised the railroad executives

that if they erected stout columns and beams between the tracks,

these would form a foundation for skyscrapers above the railyard,

standing along Park Avenue. Land developers would pay to construct

the buildings but write annual rent checks to the railroad, which

would cover costs at the new Grand Central Terminal.

The excavation required blasting a pit

as much as 70 feet deep, which brought a bit of the Panama Canal into

midtown New York. The excavation proceeded one “bite” at a time,

moving from Lexington Avenue on the east to Madison on the west. This

required tearing up the permanent track, stripping away the soil to

expose the bedrock gneiss and schist of Manhattan Island, so they

could blast it loose. The pit then filled with massive and complex

steelwork to support the two-layer track, along with the streets

above. All told the railroad created 15 acres of artificial ground

over the hidden railyard, propping pavement and sidewalks and trees

atop two miles of steel framing. This is what the new streets looked like before skyscrapers filled in the holes:

The new terminal opened just after

midnight on February 2, 1913, to much fanfare. Even as rail traffic

diminished after World War II, it survived each economic crisis

because New Yorkers valued its beauty aboveground and efficiency

underground.

So, New Yorkers, during Grand Central's

centennial look beyond the magnificent building at street level and

see the deeper lessons. The usual way to tackle a wicked problem is

to use reasonable approaches like a direct attack with legislation

that fills in all the unhappy details, or else to try and buy out the

problem with huge public subsidies. Much of the time, even most of

the time, such reasonable approaches fail.

Grand Central Terminal, the miracle

at 42nd Street, suggests that sometimes we need the

unreasonable. When I was in law school we studied the “reasonable

person” standard and that's fine for Contracts and Criminal Law,

but I like to think of Grand Central Terminal as a triumph of

the unreasonable man.