We're coming up on the thirty-fifth

anniversary of what could have set off World War III: a close call in the

predawn hours of November 9, 1979. It doesn't have a name like its fellow close-call, the Cuban Missile Crisis. Let's call it 11-9-79.

It started at the Cheyenne Mountain Complex, at the time a command bunker for the North American Air Defense Command, NORAD, inside a mountain near Colorado Springs (Photo of North Portal, Wiki Commons):

It led to a

high state of alert in SAC terminology -- likely the one called Posture 6 -- because duty officers saw what appeared to be a first-strike, sneak attack:

thousands of missiles launched from Soviet submarines and missile

bases.

As standard Cold War history

describes it, based on USAF reports and hearings: It happened after some careless person in the NORAD command post inserted a training tape into the wrong computer. The tape contained a scenario showing a missile attack from Soviet forces, and it went onto

display screens across air-defense command centers including the

Pentagon. The USAF classed it immediately as a likely false alarm

and, within a few minutes, duty officers at Cheyenne Mountain

confirmed that it was false. All

concerns were resolved before the center would have needed to consult the National Command Authorities. No change in DEFCON status resulted, and no

aircraft with nuclear weapons were scrambled.

Revisionist history: While the

standard account is accurate in broad outline (there was a false missile-attack alert that morning and the USAF realized the fact soon enough) the details are more

interesting and scary. I believe 11-9-79 was one of the five most dangerous false alarms of the Cold War like this Soviet one in 1983, which coincided with rather grave misunderstandings about the Able Archer exercises. (Fortunately, a Soviet officer held off elevating that one.)

I looked into 11-9-79 while researching my history

of war alerts for Air&Space, "Go to DEFCON 3," but I didn't go into the incident in that article because the event didn't cause a change in DEFCON status. (Why not? It happened so fast there wasn't time for DEFCON alerting.)

Here's a layout of the complex: the labeled Combat Operations Center is what the movie WarGames tried to show, in Hollywood fashion.

I went into the complex one time, as part of article research on space debris. My view of the command center and its display screens was

from a class-walled conference room overlooking the floor, which they

called the Battle Cab. (There was a fascinating point I learned there about situational awareness, but that's for another post).

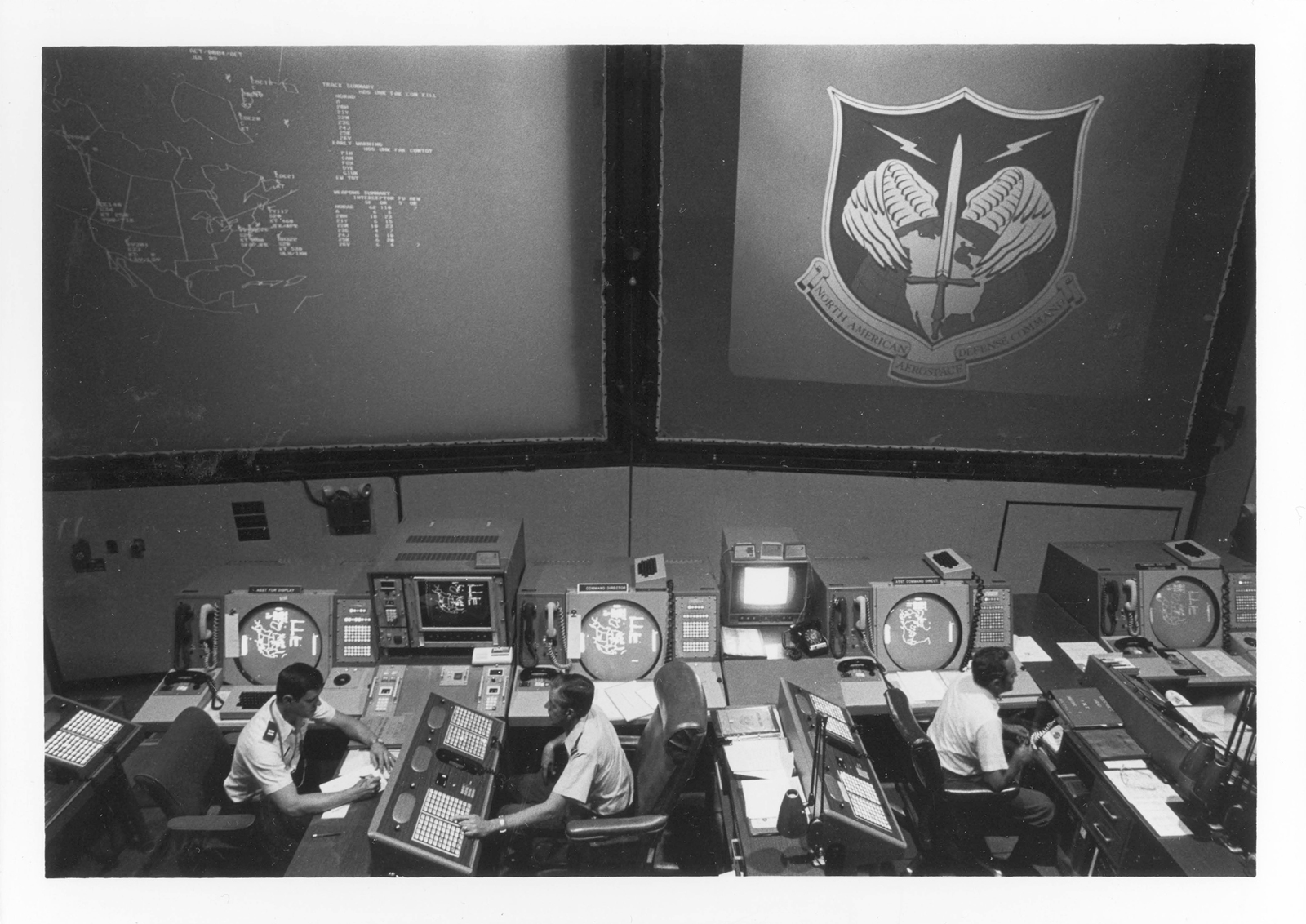

Here's what the Cheyenne command center looked like three years after the 11-9-79 incident (Photo, GWU archives from the US Information Agency):

Certainly not as glitzy as the one portrayed in WarGames, 1983:

Following is what I could gather about how things almost spun out of control inside Cheyenne Mountain -- and outside. See also George

Washington University's National Security Archive.

In September 1979, two months before the 11-9-79 false alert, the North

American Air Defense Command (NORAD) activated a new

automated-missile-warning system called 427M at the Cheyenne

Mountain command post. Here's a GWU-collected photo of Cheyenne computers in 1982:

Numerous investigations had

flagged the 427M system as problematic, years behind schedule,

and over budget. In 1978 the GAO suggested replacing the entire

thing.

The 427M system used for missile-attack detection at Cheyenne Mountain relied on two Honeywell 6080 computers to process

data from missile-warning sensors, a primary computer and a first

backup.

In a prolonged effort to sort out the problems

with 427M, NORAD was carrying out a test program on a third

6080 computer at Cheyenne. This test program was the source of the

attack scenario that got loose on November 9. It was not a “training

tape;” it was part of troubleshooting.

Although the third 6080 computer

used for the test that morning was not intended for operational use,

it was connected to the 427M missile-warning system and available on

a standby basis, as a secondary backup to the primary backup.

Exactly how did it happen?

According to NORAD in followup reports, the exact manner could

neither be determined or reproduced. I gather that the most likely reason was that the primary 6080 for

the 427M system, and then the first backup 6080, crashed. This

brought the third 6080 online. Now it was running the test

scenario and there was no tag on the screens indicating this

was a simulation. So the false information from the third 6080 went into the "Wimex" command and control system and onto Message

Generator/Recorder screens at the Strategic Air Command headquarters at Offutt AFB in Nebraska, the National Military Command Center in Washington, and

the alternate NMCC.

While the Air Force downplayed the

response as just routine by-the-book precautions, it went

beyond that. At least a dozen warplanes scrambled off

runways in Europe and North America. The National Emergency Airborne

Command Post (NEACP) took off from Andrews AFB, though without the

president or Secretary of Defense (1974 photo via GWU):

Seven Canadian Air Force CF-101s

took to the air. Quick Reaction Alert aircraft (aka Victor alert) flew

from NATO bases in Europe and set course for the Soviet border. It's

possible that some of the QRA warplanes carried tactical

nuclear weapons.

Why the big reaction? From what I can

gather, the false alert on November 9 was unique in all Cold War

history: it was the only time a completely plausible picture of an

all-out, sneak attack appeared throughout the key air defense command

posts. In all other cases of nuclear-weapon false alerts (going back to 1954), the attack information visible to controllers was strange

on its face: glitchy and erratic, or glaringly inconsistent with

likely war plans -- that is, displayed as an isolated and small attack.

We might not have heard about 11-9-79 except that a reporter from the Washington Star

happened to be visiting an air traffic control center at the time

and saw the excitement among FAA personnel, who were preparing to

contact airliners to tell the crews to land immediately (the famous SCATANA

protocol, partially implemented on 9/11).

Communications were opened with

Washington, in the form of a heads-up call to Carter's national

security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski. The alert was cancelled

before Brzezinski could call the president.

While the false alarm was resolved

within six minutes, fast enough to avoid an accidental nuclear war,

the process didn't go as well as it should have. The duty

controllers at Cheyenne were unable to reach a recommendation in the short time

permitted them, so the problem went upstairs to senior officers. It

was worrisome enough that the USAF directed that the duty officers

receive more training on how to handle alerts.

One reason that it was so

stressful and dangerous is that the false scenario included a

submarine-launched ballistic missile attack on the continental US,

fired from Soviet submarines not far from US shores. Here's one of their Delta-class subs (photo, USN):

A little more on the last bullet, the sub-launched missile factor. While our leaders touted their advantage of

being resistant to counterattack, they didn't say much about how the

close-in fielding of SLBMs (and later, nuclear-tipped cruise missiles, also

launched from subs) forced war planners toward a hair-trigger,

launch-on-warning stance.

By the 1970s most of us still thought

that attacks would come as waves of missiles launched over the Pole

from the Soviet heartland, taking 30 to 40 minutes from launch to

explosion. Actually the greater risk was from sub-launched ballistic missiles (Photo, USN):

SLBMs would have arrived at coastal targets a few minutes after

launch. While SLBMs aren't as numerous as ICBMs, they would have had

a truly devastating effect on all command centers, air bases, and

major cities within a hundred miles of the coast. There would have

been no time for the US to implement the Curtis-LeMay-style war plans

of the 1960s, which envisioned scrambling hundreds of bombers and

tankers so as to keep them safe from warheads aimed at air bases.

In summary, the world was very lucky that the U.S. didn't happen to be in a crisis with the Soviets at the time, like Able Archer in 1983 or the Yom Kippur War in 1973. (I described in my DEFCON article why the 1973 situation was so dangerous, due to developments in the Mediterranean Sea).

Otherwise, given such a very realistic picture of sub-launched missiles in flight, and so few minutes to act, I'm sure this alert would have gone to the National Command Authorities ... whether or not President Carter was available.