At the first of the Vietnam War, helicopters commonly provided rapid transit for troops attempting to employ a “cordon and sweep” maneuver to round

up the enemy.

Shortly afterward, using tactics mostly likely borrowed

from Algerian rebels, the North Vietnamese learned how to shoot American helicopters down. Americans tried new tactics and new helicopters.

While most air-assault missions failed to find and fix the enemy,

there were some units who achieved continuing success before the

U.S. began pulling out of Vietnam in early 1969. This came

in part by using the new helicopters in new ways, but also by knowing when not to use them. Some of the most valuable lessons came from from the pre-helicopter

era.

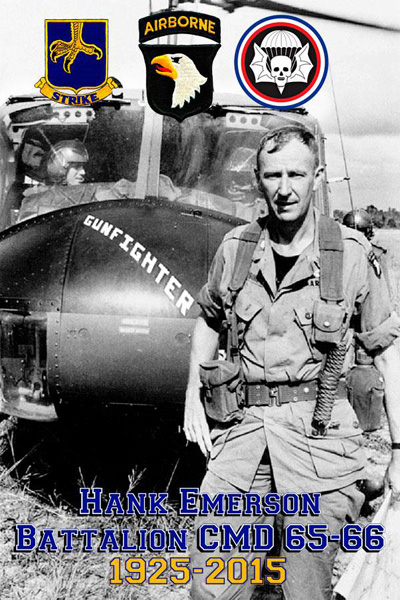

Emerson's innovations

were not heavily publicized during the war, nor in popular treatments of

the war afterward. But the men who served under him had a high opinion of him. I interviewed Gen. Emerson at length for my book, The God Machine.

And I'm glad I had that chance, since the Gunfighter died in February.

I first

came across references to the Gunfighter's story while reading through transcripts of songs taped during talent shows put on by Army aviators

during the war. Many were musical complaints about foolhardy

missions, clueless commanders, mechanical malfunctions, and mistakes

committed by novice pilots. Some songs took aim at the growing fame

of Green Berets, who the writers called “Sneaky Petes.”

Since

commanders usually come off badly in any song or skit drafted by

combat troops, one song stood out. Titled “Gunslinger,” it

referred to a lieutenant colonel named Hank with the 101st Airborne

Division. In the song, the colonel’s helicopter is shot down after

enemy fire cuts the hydraulic lines. Rather than hunker down for

rescue, Hank gathers his men, strikes up a song, and goes out to

chase down the Victor Charlie who shot at him.

The enemy replies with

hand grenades but the colonel roars his defiance and is victorious.

He opens up two canteens of whiskey and shares them with the troops

as they await a lift out.

“I

never had a better time or met a better gang,” the song concludes,

“The night we whooped old Charlie’s ass then partied in Phan

Rang.”

“The

unusual part of all of this is that ‘Hank’ was not a pilot or

crew member,” remarked Marty Heuer, a former officer of the 174th

Assault Helicopter Company who helped gather the song archive.

According to Benjamin Harrison, then a brigade commander in Vietnam

with the 101st Airborne, the songwriter clearly was referring to Col.

Henry Everett Emerson, known as “Gunfighter” to his men. I

located Emerson in Montana.

Emerson’s

first brush with the long war in Indochina came in March 1953, as a

military aide to Gen. Mark Clark. Dwight Eisenhower had asked Clark

to bring back a personal report. Emerson, who by then had experience

as a platoon leader and company commander for the 442nd RegimentalCombat Team in Korea, spent hours swapping stories with the officers

of the French Expeditionary Corps.

The

French described how the Viet Minh were cutting up their truck

convoys with ambuscades. “They had the flower of the French Army

there,” Emerson told me. “These were Legionnaires, and first

rate, but they were having a hell of a time…. Clark sent a letter

back, saying ‘This is a morass, we want no part of this.’ And Ike

stayed out of it. The terrain was all wrong, and there were long

logistics lines.”

By 1965, some strategists believed that helicopters had permanently tipped the scales to give the advantage to Western airmobile forces. They pointed to how U.S. troops brought devastating firepower

to bear at the battle of Ia Drang, but such opportunities proved

to be rare as the enemy learned and adapted.

What good was a mechanized force that struck like so many

lightning bolts, if the enemy refused to come out and fight fair?

Were American forces incapable of driving the enemy out of South

Vietnam?

Such

questions were timely to then-Army Lt. Col. Hank Emerson. In 1965

Emerson was at the U.S. Army War College at Carlisle, Pennsylvania,

preparing for his first tour in Vietnam as a battalion commander for

the 101st Airborne Division. Feeling that the standard curriculum

would not help him there, he cut classes and burrowed into the

library. Emerson read books by Mao Zedong and Vo Nguyen Giap. He read

about the French-Indian War and border wars on the American frontier.

“I was most interested in guerrilla tactics,” Emerson recalled,

“where the enemy fights like Indians.” Early in his military

career Giap had similarly spent many days reading classic military

literature, working out tactics against French and then Japanese

occupiers.

One of

the books of special interest to Emerson was Shoot to Kill, by

British infantry commander Richard Miers. Miers explained how,

beginning in 1951, the British worked out tactics to surround

insurgents they called CTs, for “Communist Terrorists," based in the

Malayan jungles. Four platoons radiated from a common center.

As the

tactic evolved, the British “Ferret Force” began using

helicopters supplied by the Royal Navy to surround and capture

insurgents. The helicopter unit was the 848 Squadron, whose feisty

motto was acip hoc, Latin for “Take that!”

The

British had progressed beyond the truck-minded use of helicopters to

employ them in setting up a cordon, or ring, with which to trap

insurgent forces in the jungles of Pahang for capture or aerial

bombing. Later this would be called vertical envelopment. Guided by

the commander in an orbiting helicopter, Westland and Sikorsky

helicopters of the 848 Squadron shifted infantry units to surround

the enemy, using jungle clearings when possible.

When the troops

needed to make a clearing they slid down on ropes and cut the trees

with saws and the head-high grass with parang knives. By 1952 the

British under Gerald Templer had insurgent leader Chin Peng on the

run, having killed four of his top commanders.

Intrigued

by the lessons that the British had worked out during their years in

the Malay jungles and rubber plantations, Emerson wrote a term paper

on the subject (which is still cited

in operations manuals of the 101st Airborne Division, entitled “Can

We Out-guerrilla the Communist Guerrillas." (Emerson's paper is not available online as far as I know, but more information can be found in this book on the Army's counter-insurgency doctrine.)

Emerson proposed a

set of infantry tactics for Vietnam that evolved from Ferret Force tactics. For one thing, Emerson told me, the Ferret Force’s “weakness was being tied to a base,

and the enemy would learn that base pretty soon.” After leaving the

War College, Emerson tried out his tactics during field exercises at

Fort Pickett and in the Dominican Republic.

In

October 1965 Emerson took command of Second

Battalion, First Brigade, 502nd Regiment, 101st Airborne Division.

The forested north-central region in which he would operate (labeled

II Corps and III Corps on American maps) was serving as a slow-motion

highway for North Vietnamese invaders who passed through on foot. It

was a year of rapidly escalating conflict. Seemingly the entire NVA

was migrating toward the rice paddies and cities of the South, ten to

fifteen men at a time. He had orders to find and destroy them.

Emerson’s

paper laid out an approach he called the Checkerboard. While

Checkerboard varied according to terrain, it relied on three

basic elements. The first was infantry: three to four rifle companies

from his battalion, broken into smaller units. All units kept in

touch by radio. There were Recondo squads who served as scouts, and

smaller groups that maintained observation posts by which to monitor

enemy movement. Typically Emerson’s battalion kept one rifle

company in reserve.

The

second element was a very limited use of helicopters to move

infantrymen around the area of operations. Whenever possible, “We

all walked,” said Thomas H. Taylor, one of Emerson’s company

commanders. “We didn’t want to insert by helicopter because the

NVA would know our location. We’d slip through the jungle and meet

at a trail junction or near a rice cache.”

The

third element was artillery positioned on hilltops that could lay

down a steady stream of shellfire for miles in all directions.

In Emerson's original conception, these elements were to play out across a

checkerboard on which U.S. troops would move like game pieces,

choosing their own moves to block the movements of NVA forces from

north to south. This from the Army's Center for Military History:

While in

practice Checkerboard did not play out as simply as a sand table

exercise, Emerson stuck to his first principles: keep fighting men in

the field for as many days as possible, move fast and stealthily, and

direct the enemy into well-laid traps rather than blunder into random

firefights. Each time upon walking into a new area, the American

scouts and observers spent days inspecting the terrain to find paths

being used by NVA troops in transit.

Once the

patterns and bivouac locations were known, they radioed back to

headquarters. If artillery was in order, a request might go: lay down

a barrage at 0200 hours on the following enemy areas, but not the

adjacent friendly ones.

The

artillery fire was not to destroy the enemy in camp but to roust him.

“So the VC would go running down the trail, just like anybody else

would,” said Brien Richards, an infantryman for the Second

Battalion. “The artillery would keep ‘em moving and they never

knew where we were.”

The Recondos were laying in wait inside

“friendly” areas, along the expected path of NVA movement.

Emerson’s men had prepared fields of fire. They used grenade

launchers and automatic weapons, but the most devastating were

Claymore mines, which when detonated, sprayed shrapnel like massed

machine guns.

The

Claymores were arrayed in L-shaped patterns, and detonated by wire.

Employing them required the ambushing squads to allow the enemy’s

point-men to walk through the U.S. lines. Taylor says Emerson’s

vision came closest to his 1965 paper in an action in War Zone D,

appropriately called Operation Checkerboard. In such open country

there were no well-defined corridors of foot travel, so the battalion

set up a checkerboard of friendly and enemy grid-squares.

In all

its variations, the Checkerboard usually worked. According to a

combat report in Newsweek, by mid-1966 Emerson’s battalion

was beating the enemy on its home field: moving like ghosts, laying

ambushes, and hauling rucksacks with maximum ammunition and minimum

rations.

A typical ration was a little canned meat and a few pounds

of rice, which lasted one man five days until the next resupply

mission by air. “We went out heavily gunned, carrying ammo, ammo

and more ammo, then water,” Richards told me.

“They

stayed totally on the move,” Emerson said of his men. “Instead of

me picking out an ambush for them, the decisions were decentralized

to the lowest level.”

Helicopters

kept Emerson’s men hustling to NVA footpaths all over north-central

South Vietnam, from A Shau Valley in the west to Tuy Hoa on the

coast. What the helicopters didn’t do was to run the men back to

camp for hot food, showers, and beer. According to Jim Gould of the

Recondos, the troops stayed in the field for as much as three weeks

at a stretch, followed by a three-day break. “Then it’s back out

we go,” Gould says. “In the early days we did not have what was

known as fire bases. We just traveled around the country: set up an

LZ, ran the mission and moved on to another LZ.”

Emerson

extended his tour an extra six months, but the Army moved him out of

country in October 1966. He began laying plans for a return.

I'll

describe Emerson's second tour, and its fiery end in Vietnam's Mekong Delta, in a later post.